I read recently in The New York Times that psychiatrists are now prescribing Ozempic, the Instagram-famous diabetes medication, to mental health patients for weight loss. I had to stop and silently scream. Has “over” a narrow societally accepted weight become the most depressing state imaginable in our fat-phobic society? Half of the mental health facilities they spoke to were already doling out The Oz (ok if I call it The Oz? The comparison to a land of magical deception seems apt), and more were considering it, even though Europe is “reviewing data” on a possible link between Ozempic and increased suicide risk. This is before acknowledging the high co-morbidity between eating disorders, body dysmorphia, malnutrition and other mental health diagnoses.

The article made me realize that it’s past time for me to comment on the approaching storm: the katabatic winds of The Oz and its inescapable friends like Wegovy and Mounjaro pushing towards us. Their accelerating popularity has these social media darlings at the forefront of millions of conversations between patients and medical professionals, even people who formerly felt peace had been made between food and their bodies. I’ve met many people feeling conflicted about body image in a way they never did before. But these new weight-loss drugs are here to stay, and they threaten to collapse the world the Health at Every Size movement has worked so hard to build.

As difficult as it may be to believe,

Ozempic, or semaglutide, is part of a class of injectable diabetes medications that have only been on the market for six years. These “GLP-1 (glucagon-like-peptide-1) receptor agonists” have been effective in improving blood glucose control by stimulating (“agonizing”) a hormone (GLP-1) that tells the body to produce more insulin when blood sugar levels are high. This has helped many people with diabetes, but this is not the reason for Oz’s wild popularity. The reason that doctors are currently writing more than 60,000 new prescriptions every week for Ozempic and friends (including Wegovy, a higher-dose semaglutide formulation, and Mounjaro, a newer mixture of semaglutide +tirzepatide), many off-label, some under a rushed diagnosis of “insulin resistance” based on patient body size only, is clear: weight loss.

The thing is, GLP-1 naturally does two other things in our body besides stimulating insulin production: it sends a message to the brain signaling that we are full, and it also slows down how quickly food moves through the digestive system. This makes sense when you think about our body’s amazing self-protective instincts: slower entry of food from the stomach into our absorption powerhouse of the intestines means less sugar entering the already-full bloodstream, and a sense of satiety means we might stop eating, giving our body a chance to process what it already has inside.

Drug companies studying Ozempic quickly noticed that people with diabetes were losing weight on it, and the dollar signs started sparkling. The reason for this weight loss isn’t that Ozempic directly burns fat, or has some other magical slimming power. Because of GLP-1’s secondary effects, it just makes it easier to eat less, sometimes a lot less. People on these drugs quickly feel full from the slow-moving food sitting in their stomachs, so they eat an average of 35% less.

This is where things get complicated. If you are a person with diabetes, and you lose weight as your blood sugar control improves, this weight loss could be a health-neutral side effect of overall improving health. In other words: the fact that your blood sugars are normalizing is wonderful, and it will likely make you feel better. One facet of uncontrolled Type II diabetes can be a sensation of ravenous hunger because our cells don’t have the insulin they need to take up the glucose available to them in the bloodstream. Our belly could be full, but our cells might be starving, sending continued hunger signals to the brain. Insulin “opens the door” of our cells to let sugar inside. By slowing down our eating and releasing more insulin through GLP-1 stimulation, we give our body the choice to slowly metabolize more of what we eat.

Our weight can often change in one direction or another as our health improves. This doesn’t make body size a problem or a valid marker of health—but it can be a symptom of health changes. Respecting our body means loving care regardless of size—and centering the reality that whole-person health often improves without changes to weight at all.

Unfortunately, in both people with diabetes and especially without, the weight loss experienced on semaglutide medications could simply be starvation. This is the same mechanism as any diet: eating less food than our body actually needs, so we are forced to burn fat (and muscle) stores. With simple food restriction, our body eventually compensates by increasing hunger hormones and decreasing hormones like GLP-1 that make us feel full, in a wise attempt to scream at us to PLEASE EAT ENOUGH FOOD. Ozempic overrides that hormonal messaging, cutting communication lines. Our body may be suffering, but it has no way to tell us. And so we continue eating less. There isn’t any standard nutrition guidance or malnutrition warning accompanying semaglutide medications (yet), but as The Guardian colorfully puts it: Ozempic is “the chemical realization of a behavioral psychologist’s wildest dream, A Clockwork Orange for junk food, an eating disorder in an injection.”

Despite a paucity of studies (as with all dieting research) following patients who lose weight on Ozempic to see what happens to their bodies long-term (spoiler alert: as soon as people stop Ozempic weight re-gain seems to be immediate), companies are aggressively advertising these medications (a recent Novo Nordisk stockholder presentation trumpeted 124% sales increase following “relaunch” of Wegovy in January 2023), and they have become extremely popular, because, no surprise, weight loss is popular. Short-term studies have found that weekly semaglutide injections “combined with diet and exercise changes” result in an average of 33.7 pounds of weight loss in a year. These are similar results to most medical diet programs, but the costs are higher: from $900-$1300 per dose, or up to $16,000 per year, typically not covered by insurance.

So whatever else is true about semaglutide medications, one thing is rock solid: these meds are gold for drug companies, who are poised to mine billions from the feverish fat-phobia fueled demand.

Before we talk about the experience of actually taking these medications-

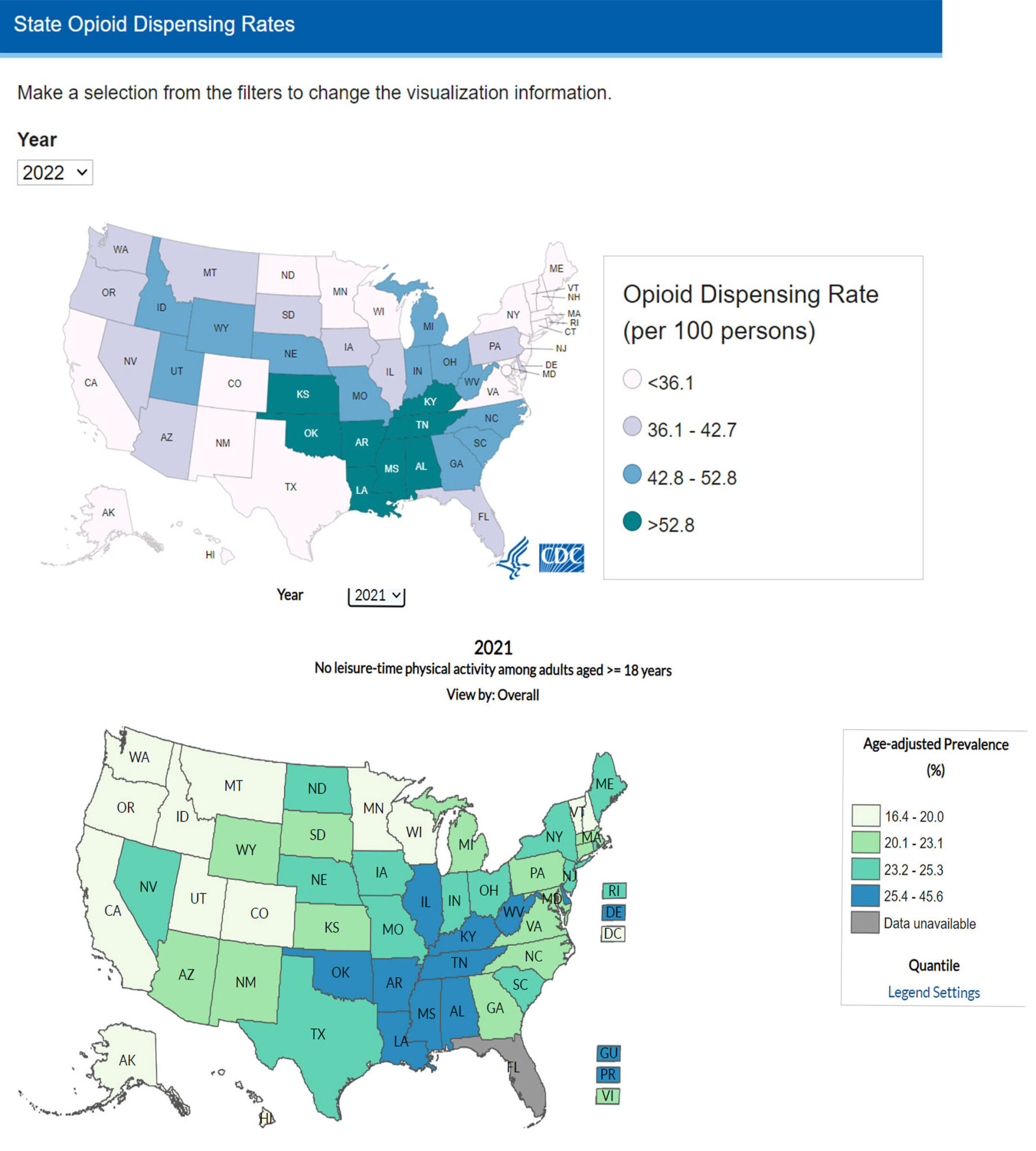

—the short and long-term side effects, the risks to weight neutrality—I’d like to take a critical thinking pause. If the hurricane force increase in semaglutide prescriptions and profits causes you déjà vu, you aren’t alone. Remember the last time the US was swept away by a wildly popular new class of drugs? How did that turn out? I’m talking of course about the Opioid Epidemic, which at its height in 2010 had doctors writing nearly one new prescription per person in the country that year. Investors, researchers, medical professionals and drug company executives were all carried off by the seductive (and magical) equation of pain + pill=profit, to the long-term detriment of millions of people. In that case, just like the current craze, a drug was offered as a solution to what was actually a bigger societal problem. As writer Tressie Mcmillan Cottom puts it in her New York Times piece “Ozempic Can’t Fix What Our Culture Has Broken:” Ozempic is “a weekly shot that fixes the body while skipping right past the meanness of improving the way people have to live.”

The truth is, most of our health outcomes are socially determined: it isn’t fat that causes us to develop diabetes, heart disease, and chronic pain: in addition to genetic vulnerability, it is productivity capitalism and its inherent inequities (aka “social determinants of health”): long hours working in sedentary or back-breaking conditions, a food economy that necessitates quick store-bought foods, the shame and discrimination heaped disproportionately on larger, Black, disabled, and female or trans bodies. Our health is a direct reflection of how much privilege or oppression we experience. Opioids were offered as a quick fix to keep injured or pained bodies productive while ignoring these same bodies’ needs for rest, recovery, and equality—much more complicated structural issues to address. In the same vein, Ozempic-type medications are attempting to offer a short-cut route to the privileges of thinness (which is statistically associated with higher pay, better jobs, and higher social status) while overlooking the social injustices that led to these privileges in the first place. America has a bad habit of blaming individuals for larger structural problems, and shames individual bodies rather than systems.

For a visual representation that speaks volumes, check out the following maps from the CDC showing Opioid Dispensing Rates from the most recent year available (2022) and places where there is “No Leisure-Time Physical Activity Among Adults” (latest from 2021). As you can see, the highest opioid use and least opportunity for physical activity breaks overlap almost perfectly. It also isn’t a coincidence that these metrics overlap in the states with greatest poverty. Our unbalanced economic system forces people over and over again to set their bodies aside in the pursuit of economic survival. If this resonates for you—it really and truly isn’t your fault.

Ozempic entered my consciousness a few years ago;

when I started to notice a big uptick in the number of referrals I received for gastroparesis. Gastroparesis is a slowing or even dangerous stoppage of gut motility that can result in severe abdominal pain and vomiting as the body attempts to propel stuck food back out the wrong exit. Concerningly, many of these patients had a common history: a recent weight-loss attempt on a semaglutide medication.

Most people experience a number of side effects on Ozempic, from mild to severe. One of Ozempic’s most troubling side effects is directly related to its mechanism of action: the slowing of GI motility triggered by the GLP-1 hormone. “Motility” describes how quickly food is propelled downward in the GI tract—from the stomach to the small intestines to the large intestine and out of the body. It is controlled by our autonomic (unconscious) nervous system, and when working smoothly, operates on a circadian rhythm similar to sleep, a one-way conveyer belt moving food downward in time for the next meal. But when semaglutide is introduced into the system, it puts a pause on this cycle. Food in the stomach stays in the stomach longer, which can increase pressure on the lower esophageal sphincter connecting the stomach to the esophagus, which can in turn cause reflux and even regurgitation. Because the conveyer belt has stopped, waste can stick in the colon longer, causing bacterial overgrowth, constipation, bloating, or abdominal pain. According to FDA data, the agency had received over 8,000 reports of gastrointestinal disorders by June 30th of last year. Some of these reports describe ileus, a complete intestinal blockage that is a medical emergency. This has triggered not only major lawsuits against Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly, but also an FDA box warning label. Canada recently issued its own warning that GLP-1 medications can cause vomiting (and thus possible aspiration of vomit) during surgery after a patient suffered just such an outcome. Even complete stomach paralysis seems to be about 3 times more likely in people who take semaglutide compared to those on older types of weight loss medications like bupropion-naltrexone.

The combination of slowed GI motility and weight loss that Ozempic promotes can be especially damaging to the gallbladder. When food is moving more slowly through the GI system, “biliary sludge” can build up in the gallbladder. This can cause stones and inflammation, even the life-threatening infection cholecystitis. Deaths have been reported from gallbladder disease, even in company-sponsored studies. Companies like Novo Nordisk claim that GI side effects are “transient and mild” and their own studies show a decrease in symptom severity after the first 12 weeks. Nevertheless, longer studies following patients for 30 weeks show as many as 20%-60% of patients suffering from nausea, and over 11% diarrhea and vomiting. 12% of patients drop out of Phase III semaglutide trials due to GI complaints.

It is also important to keep in mind that while GI disturbances may be listed as common “side effects” on Ozempic’s warning label, in reality, it is likely that gastrointestinal distress is central to its mechanism of action. After all, the nausea, vomiting, and reflux that accompany slowed GI transit can cause aversion to eating at all. A 2012 study found that nausea is integral to semaglutide medications’ ability to reduce food intake, and a more recent study showed that people who experienced nausea lost more weight than those who didn’t.

While not everyone who takes GLP-1 medications will suffer painful side effects, anyone who has ever experienced the discomfort of gastroparesis can imagine how awful eating could become. In more severe gastroparesis, dietary choices are limited, because higher fat or fiber foods cause painful fullness, and meal sizes must be small. A new introduction of food into the system, even just a few bites, might trigger extreme nausea or bloating, or “stick” in the esophagus, leading to a panicked feeling akin to choking. Once the food does sink into the belly, the body may not be ready, propelling it back out as vomit. Nausea is constant. The possibility of fatigue, weakness, low blood sugar, even fainting from lack of enough food is ever-present. In the patients I have seen with suspected semaglutide-induced gastroparesis, it has taken months of careful, painful eating to recover smoother digestive function, and even then recovery might not be complete.

Beyond the GI system, Ozempic and its friends carry a number of concerning risks. Deaths have been reported. Fatigue, loss of muscle mass, and hair loss are common, though this could simply be from malnutrition. Ozempic increases heart rate, which might increase mortality. Animal studies have linked Ozempic to an increased risk of thyroid cancer—human studies won’t be complete until ~2035– but the FDA currently requires Ozempic to carry a box warning for thyroid C-cell tumors, and has increased monitoring for thyroid cancer incidence in the US for at least the next 15 years in response.

For people with diabetes, Ozempic generally seems to have net protective effects, especially for prevention of chronic kidney disease, but it in the short term it has caused hospitalizations for acute kidney injury, possibly related to dehydration and vomiting. One trial also showed an increased risk of diabetic retinopathy. Mounting data on the damage it can cause to the pancreas is even more concerning. In studies, one in every 200 people who take semaglutide drugs developed pancreatitis, a dangerous inflammation of the pancreas that can lead to hospitalization and death. Some trials also suggest a link between Ozempic and increased risk of pancreatic cancer, though it will take years to sort this out.

In what world is this a picture of the increased “health” Ozempic is supposed to provide?

To be fair,

not everyone experiences life-disruptive side effects on semaglutide medications, and many might indeed see their side effects fade over time. But so much is still unknown. It is well-established that weight loss on a restrictive diet (one that cuts food intake below our needs) reverses as soon as the diet is stopped, and often regardless of whether the diet is stopped, due to metabolic adaptation. Research has shown that the weight-loss experienced on Ozempic is similarly temporary: as soon as patients stop semaglutide medications, most or all of their lost weight returns. More concerningly, any cardio-metabolic improvements also reverse within a year a two of stopping these medications. It is currently a little-disguised secret in the medical community that a prescription for a semaglutide medication is a lifetime prescription. But no one in the history of the world has taken Ozempic for 50 years. We just don’t know what that might do to a person.

When we try and starve our body smaller, our wise body always rebels to protect us: slowing down body processes so our energy use can better match what we intake. Ozempic and other semaglutide medications may at least temporality shut off our brain and belly’s awareness of the danger, but it doesn’t mean our body isn’t constantly adapting to establish a new metabolic normal, one that relies on less food long-term. As with all diets, dramatic weight loss may begin the story, but the body will likely work to re-establish its genetically desired weight. In the process, we might experience the same organ-damaging weight cycling that accompanies any food restriction. As with other types of weight-loss dieting, the Ozempic story likely ends in diminished health, shame, and frustration.

I’ll admit I’m not feeling positive about the Ozempic bandwagon,

but even if drug manufacturers do figure out a way to tweak semaglutide medications to eliminate all negative side effects (and you can be sure they will try!), the side effects aren’t really the point. At the core of this controversy is the sad truth that our society demonizes and discriminates against larger bodies. Giving people another pill or injection to delete those bodies doesn’t delete the underlying prejudice and inequity. A person in a fat body is a type of person, not a disease. It’s a short leap from designing ideal bodies by size to designing an increasingly narrower range of acceptable heights, skin colors, ethnicities, and gender presentations. It’s an even shorter leap to “fixing” bodies of their disabilities, or society of disabled people. What does our world lose when it loses body diversity and human diversity? Is this perfectionistic, eugenic world really one in which we wish to live?

Semaglutide medications can be a powerful tool in the fight against diabetes, and used correctly (once we have enough research to know what that means!) might even help mitigate the risk of other diseases. But they aren’t the only tool in our toolbox to address “food noise,” chronic disease risk, and body dissatisfaction. We already have a much safer and more just one: a weight-inclusive, intuitive eating approach that teaches individuals how to feed and care for their bodies with compassion, and challenges society to remedy root causes: prejudice and social inequity.

If you’d to discuss what this means, or the complicated pros and cons of semaglutide medications for your unique body, contact me today.