I recently yanked some overgrown cabbage leaves out of the vegetable garden and chopped them into a generous pint of chow chow. No, not a “puffy-lion” dog, but a classic Appalachian hill country condiment pickled from a mix of cabbage, spices, green tomatoes, onions, and peppers. It was my first attempt at making the chow, and it turned out beautifully: a sweet-sour canary yellow vegetable slop begging to accompany barbeque. When I was a kid, we always kept a little jar in the fridge. Though I wrinkled my nose at anything other than ketchup in those days, the comforting miasma of background pickle must have yellow-pigmented my heart, because a few years ago, I walked into the Floyd Country Store in Floyd, Virginia and caught my breath at the deli counter when I saw the sign: chow chow, $2.50 a scoop.

I hadn’t seen that word in ages, but putting the crisp-fresh sugar-mustard relish to my lips was like opening a locked truck. My Virginia childhood, complete with green beans on the vine, red dirt by the lake, and pecans in winter came pushing back to me. It was an ache released, a wide river pressing against the mud of my body.

I had never been to Floyd specifically, or even eaten a platter of hot pink pickled eggs and beets, yellow chow, and vinegar chips for my lunch, but something about the experience was familiar in a way that Pacific salmon and blackberries have never been. It made me wonder: from what foods is my soul really built?

When you grow up in the South, food is and is not a big deal. Classic Southern food is one of the most clearly recognized, long-revered, and long-ridiculed food cultures in America, stereotyped and sanctified. Anyone from Fargo to Santa Cruz could probably rattle off a list of its picnic-inspired classics like fried chicken, coleslaw, buttered biscuits, and banana cream pie, but when you grow up in the South, most people don’t really care about food. Ideas like “eating locally” and “wild-caught” didn’t have traction where I grew up in Virginia (the part south of the Mason-Dixon Line). We destroyed our farms and forests, polluted our Chesapeake Bay, and bought in bulk at Wal-Mart. We ate Iowa corn grits at Cracker Barrel and macaroni and cheese at Golden Corral, but somewhere at the edges, the jars of Old Bay and chow chow shaped an identity.

I always wanted to grow up in one of those Southern Living plantation homes, where towers of red velvet cake and pitchers of iced tea glistened from sunny dining tables. Instead, we lived in a cracked grey house with a sloped porch, a place where my dad shot at squirrels to protect the pecan tree, threatening Brunswick stew after. Food in our house was very much, and very much not, a big deal. My mom’s huge vegetable garden was unique on our block, but she raised tomatoes and corn from a place of budget-conscious duty, not because she thought our “local” tomatoes would be more nutritious. My dad, a Yankee transplant, kept a tattered copy of Southern Cooking on his shelf and tried to incorporate lima beans and corn pone as much as possible, but this originated in penny-pinching rather than heritage. I looked down on our simple garden-prepared foods growing up, and lusted after the name brand cereals and spaghetti sauces of my peers. Nevertheless, the smell and spirit of Southern food was pooling inside of me like melted butter.

When I left to find my fortunes in Northern lands after high school, I was excited to escape what I saw as a stunted and backwards food culture. I thrilled at the idea of wild-foraging seaweed on the Pacific coast, picking huckleberries on snow-capped mountains, and participating in community gardening and 100-mile diets as an act of local food resistance. I gobbled up all the information I could find about the nutritional superiority of expensive organic kale, Oregon hazelnuts, and California avocadoes. When I returned in my 20’s to visit the land of my birth, I looked down on what I saw as a vast piedmont of refined flours and ignorance.

But over the years, as I’ve aged and grown wiser, my stance has softened. One of the miracles of learning Intuitive Eating and a size-inclusive approach, for me at least, has been gaining the ability to externalize and separate moral judgements from food. I think this is perhaps a skill that goes beyond even food or bodies, that might help us all in our divisions in this country. The distain I held for cornbread and butter beans, or cans of Coca Cola, wasn’t really about the food. Food (like people) can be unadorned, simple and plain, or mixed with unnecessary and nutrient-poor ingredients (or ideas), but it is still food, and it can still nourish us, whether that nourishment is physical or spiritual. When we feel anger or disgust towards a food or a food culture (or what we see as a lack of culture), we are misplacing our judgement. The enemy isn’t the bag of instant grits, but the poverty and overwork that thrusts a people towards only the cheapest and quickest options. Food heritage in Hampton, Virginia is humbler than that in Seattle, Washington because of the crippling shadow of economic depression, not because of “sugar addiction.” Fast food is popular in America not because the macaroni and cheese at Golden Corral is filled with irresistible sin, but because it is cheap, and when you grow up sharing it with your parents during a celebratory birthday dinner, it will always glow somewhere inside of you.

I’ve reached a point in my food journey where I can now be tickled at the sight of the little packets of instant grits on the breakfast line in a North Carolina motel, even if they don’t taste that great, and also luxuriate in the creaminess of stone-ground grits made at home with raw milk cheddar. Or I can stop to fuel up for the drive ahead at a Golden Corral (pre-pandemic, at least!) awash in warm memories, while also recognizing the sad Capitalism of a world that drives a restaurant to such low-quality ingredients, and my body’s digestive discomfort (and desire for fresh apples) shortly afterwards.

Food is complicated. How we eat, what we desire, what makes us feel good—this is so much deeper than we might at first think we know. Health food culture and the cult of nutrition has brought us some great things—more variety, more antioxidants, better poops—but it is ok if your soul isn’t crafted from chia seeds and green smoothies. I love a good kale smoothie sometimes, but my own food soul is more layered than that.

During that last Southern road trip I took a few years ago, shortly before passing through the old-timey Appalachian Hill Country around Floyd, I ate one of the best meals of my life on our friend Sara’s farm. The Blue Ridge Mountains enfold hills and hollers filled with rural folk who still keep the old agricultural South alive: land with a garden for pickling peppers and a stand of pawpaw trees out back. People who have been “eating local” all this time. I had never lived in this old South, but hearing the bluegrass and tasting the pecans of these places awakened food memories and desires long buried inside me.

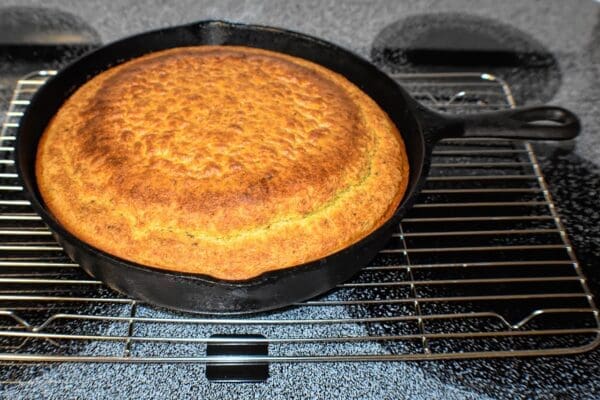

The meal was a simple one, cornbread alongside collards and Crowder peas grown right out back in the fields, but the depth of those flavors spoke to me. I tasted the red clay soil in which the peas were grown; I imagined that mud between my toes and the sun on my neck. I thought of how hard my mom worked in the garden to keep our table full of fresh foods against all odds, and the odds that have always been stacked against a good relationship to food when you grow up in the South. I hadn’t tasted Crowder peas in years, maybe generations. I remembered how wonderful it feels to break through corn pone’s crust into its butter-creamy center, how sustaining a lima bean casserole could be, how perfectly rich and zingy is a dollop of pimento cheese. I was grateful for all the Virginia cornbread dinners, mayonnaise cakes, Washington huckleberries, wild Pacific seaweed, and cans of peaches that had led me to this point. I ate until I was completely full.

Since returning home from that trip, I’ve thought about beans and corn a lot more often, and incorporated more Southern-style foods into my weekly meal plan. I ordered some Crowder peas and experimented with pickling eggs, beets, and garlic in addition to the Chow, and welcomed back pecan pie at Thanksgiving dinner. I’m planning for mint juleps come summer, and collected a list of favorite macaroni and cheese recipes to try. It feels right to round out my food binders of nutrition-school quinoa pilaf and salad jar creations with more soul food, the food of my own particular sun-soaked kaleidoscopic soul.

If you’d like to explore the many layers in your own relationship to food, contact me and let’s come up with a menu.